Coliving provides purpose-oriented living spaces for those of us whom value (some) openness and collaboration. Spaces embracing cooperative coliving involve us as stakeholders, and as you may have guessed, employ the co-operative principles.

This approach is pragmatic and practical, providing a framework for resilient and dynamic coliving space operators and their communities. We do not consider in what way a group of owners or a business may use this, and we believe there is a choice between a focus on impact as a mutualised society, and as a commercial project to reward backers, all whilst maintaining a standards-based service.

The model is intended to help guide the establishment of coliving spaces operating as social enterprises — member shareholders having flexible use time stakes, alongside a revenue-generating business. The model provides rules for incorporation and operations however these are not yet published.

For a purely commercial approach the model should be simplified and many details here would not be applicable, requiring mainly only articles binding shareholding to rental value, ensuring lifetime proportionality and booking flexibility amongst co-owners, yet also opens value transfer in networks.

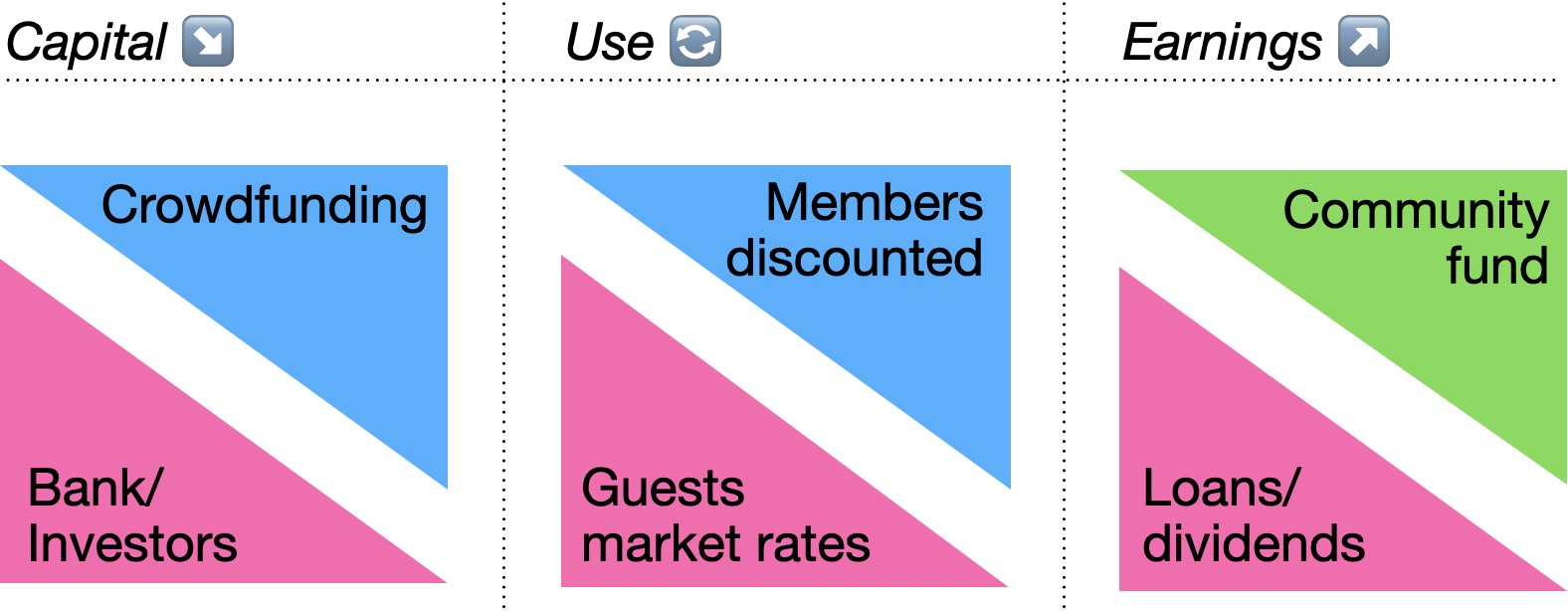

The property owning entity's shares are issued in proportion to a defined capacity, split between two core classes of co-owners having distinct purposes — fractional use members, and investors receiving (capped) returns from guest rentals, with any remaining surplus allocated for reinvestments as a community fund.

This structure avoids a conflict of interest arising from separate stakeholders desiring both use and returns, such as generating dividends to then spend whilst eliminating the capacity to be bought with them.

Here members may own both classes, but must choose in what proportion. This ensures the property is sustainable with a revenue stream grounded in the markets, and derived from its responsibility to investors for returns, yet which also benefits the community creating a virtuous purpose, and avoiding a harmfully singular dependance upon member fees.

| class | capital | fees | use | earnings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| members | ✅ | ✅ discounted | ✅ fractional | 🔄 non-use |

| founders | 🔄 sweat | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| investors | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| guests | ❌ | ✅ market-rate | ✅ rentals | ❌ |

The model may include an additional dedicated-unit member class (e.g. cohousing), which by virtue of being a unique unit class, would have good rental demand for their owners thus generating reliable revenue when not used; however the intention of such stakeholders should be carefully evaluated and use restrictions enacted to avoid speculation, though may not be an undesireable funding approach.

A coliving share purchase of €

gives annual use-value of € / nights

For demonstration only using average rates. Units could vary ±30% as would seasons, for 60% more value/time (cheaper, e.g. pods during winter) or 60% less value/time (more expensive, e.g. studios during summer).

Operating costs and contributions / charges are outside the scope of the model. Some operators may have chefs and dedicated staff, include contingency fund contributions, yet others may not.

An incorporated entity (e.g. a co-op) has the deeds to the property in its name on behalf of all the co-owners whom hold shares in it, giving direct democratic control of the property. This model is commonly used for holiday-homes but is usually less flexible requiring large fractions, such as 21-5 (whom manage €500m of fractionally owned properties) and MYNE.

Offers part-time use of a property (e.g. for digital nomads and those only wishing to stay for a limited time each year) as a co-owner, or as gradual acquisition towards dedicated ownership, and so may also be combined with dedicated units owned outright.

Booked use is not free of costs, as properties have operating costs. In a primarily mutualised approach, use is at-cost, whilst in a purely commercial approach use would be discounted against retail rental rates.

Fees should also include contributions to a maintenance fund, eliminating unplanned surprises. When mutualised, generally fees would be a fixed cost per week, however specifics may vary and could be an advance fee defined in an annual budget split between members, with end-of-year adjustments.

Share issue / purchase costs may vary, e.g. early supporters receiving a discount. Should additional capital need to be raised (for unplanned works / improvements), use value per member is reduced unless the corresponding proportion of the new issue is also acquired. (Generally should not be needed with the maintenance fund.)

The effects of the relative size and split in the two core classes are significant. The investor allocation defines the member flexibility and must therefore represent at least the off-season capacity value.

A minimum proportion will generally correspond to the off-peak seasonality. If this is 3 months (e.g. winter), and investor shares are 25%, the last member to book will have no choice for an in-season date, however in reality some members will choose to book off-season due to getting a stay up to twice as long as in season.

The proportion must also consider that a surplus should be generated to pay investors and contribute to the community fund, if this were only generated from off-season rentals it would be very poor, however as noted there should be sufficient distribution to result in some rentals in-season, yet this needs to be supplemented thus the minimum should be a somewhat larger than the off-season alone…

Under no circumstances can all capacity be issued to members as this would result in no flexibility, effectively becoming a timeshare. Unallocated time should generally be fairly generous, and whilst expected capacity in peak season may be allocated at 100%, in the shoulder season it may only be 85%, with off-peak at 50% — thus having fair capacity for both member flexibility and investor returns. This must be anaticipated per the seasonality of the locality and member use, yet is freely adaptable year-on-year.

It is highly recommended to reserve (not issue shares against) at least one bunk/pod at all times for additional booking flexibility as even members whom normally prefer a private room will book this if it means they can have a private room for at least part of a stay.

Could be opened simultaneously for commercial (public) rentals and fractional (member) use, or members may be permitted to book in advance thus gaining more choice of dates, with public bookings taken for example only from a few months prior.

Where the timeframe for public bookings is significantly reduced, such as 2 months prior then fractional members are priortised and there may be difficulty selling unused capacity for the business returns. With no limit, the business has equal chance but this potentially reduces member opportunity.

Public bookings should be restricted to a maxmimum of the capacity held by preference shares, ensuring members have their capacity available for booking. The mechanisms for managaing this may be complex, yet could simply use rolling timeframes.

Could be freely swapped between fractional (coliving) and investor (dividends) classes, providing the new share issued do not exceed a minimum and maxmimum rentals capacity threshold, ensuring there's always booking flexability (the minimum, e.g. 30%) and that there's not an excess of capacity which would requiring new management practices but may be fufilled by existing ones such as organic demand (e.g. 50%).

The investor proportion additionally represents investment into a social enterprise, having benefits for all stakeholders. The function of which must be defined. It is suggested to use preferential shares (preferred stock) with thresholds and caps, but may simply be structured as loan repayments or dividends.

To ensure the community fund has adequate value to enliven the space, its structure should ensure a proportion of profits are guaranteed to be retained towards it. In a mutualised structure to ensure investors gain a desireable return, an annual return up to a baseline threshold e.g. 5% could be utilised, paid out as priority from surplus. Remaining surplus would split payouts between the community fund and investors, potentially only up to a higher threshold cap e.g. 10%, either over a fixed term or for life.

This mechanism ensures there's incentive in running the social-enterprise for everyone's benefit.

The motivating factor for members should be use, not returns, however normal use must offer sufficient benefits, and it is inevitable that members may not make use of their stake all the time.

On an assumption that members would otherwise pay retail rental rates for an annual coworkation, with a shareholding and nominal membership fee, the shareholding cost could be returned after around 8 years of use, thereafter representing a significant discount (being the difference between the membership fee/contribution and the retail rates).

Where the operational costs include future maintenance, the appeal and affordability appear to fall significantly versus owning private property, however in reality still remains good value, assuming one actually uses most of the communal facilities. If one does not, one is paying a (small) premium for them.

This evaluation is only applicable to those whom value the cost of coworkations, not digital nomads whom seek geoarbitrage with upgrades to coliving only where affordable. Whilst it remains accessible to the latter, it generally involves exchanging the convenience of a private rental for the community value in a lower cost room, thus such an offer would have significantly less takeup amongst digital nomads than amongst professionals seeking to regularly escape their office and city bound lives. The audience of any given property project must be targetted apropriately and it is possible such a project may exclusively serve digital nomads providing the real estate acquisition and operations can utilise geoarbitrage.

Is handled by an internal market in which use is resaleable exclusively amongst members, so avoiding licensing requirements.

An internal market offers a generally desireable discount to members over retail rates thus ensures good potential demand when longer stays are desired but a member does not themselves hold adequate shares, whilst also increasing capacity (booking availabilities) so does not strictly need disincentivisation. It also plays well with capitalistic desires, by not eliminating them entirely, merely restricting them to existing members.

As every member would set their own resale cost, those having the lowest will sell first driving costs down the larger the market is. (Notable amongst multiple properties.)

To ensure community engagement, prevent revenue speculation and ensure the split between use and return shares, a minimum owner use must be applied, and when exceeded their shares be withdrawn to be made available to members wishing to join.

With 100% non-use and e.g. a 30% discount on retail, minus member fees (e.g. €200/mo), a €4k stake (1 month) could generate €500 p.a. thus providing a return after 8 years similar to use. If this is notably better than use, additional controls may be required, such as a commission (going to the platform.coop and/or community fund).

Where shares can be sold to anyone the community is diluted as people may buy them only for their appreciation, or for uses that are not core to the community (e.g. holidays).

Whilst by no means essential and in fact may dissuade some backers if implemented, to eliminate sale speculation better supporting community use, all shares are non-transferable (cannot be sold to others) and withdrawable, returning their cost (for which terms, and some manner of appreciation may apply). These are known as 'community shares' in the UK.

It would nonetheless be possible to allow any sale price to waiting members should they so agree, and for the seller to gain the proceeds above the original value thus preserving further capitalistic intents (may however involve regulatory complications).

Providing all members ensure the community remains desirable, it will be easy to exit as there will be a waiting list of new members whom wish to join. If the community is not desirable it will be impossible to exit thus it is in everyone's interest to maintain a desireable community, being unlikely that members will remain for life.

Should the property value have increased to the point where it becomes desireable to leverage, a special resolution may be used to divest of it, and for example acquire other properties in lieu, or to terminate the project entirely. (It is however worth noting that a good coliving property would be harder to sell due to potentially needing to be converted again, unless simply to a purely commercial operator of which more are likely to emerge.)

Where fundamental aspects such as fractional co-ownership and use availability are shared, independant properties and operators could form a federation within which use-value may be exchanged amongst. Furthermore misbalanced demand may still be managed in such a network by adding exchange fees.